An Accidental Encounter with Kerouac

By Madison Mainwaring

Paris is the opposite of an open road. It is a collision, a set of barricades, serpentine passages constructed and built up over centuries. All paths lead to this mess of an intersection, dense with smoke and tourists, streets that disappear. One finds a way to the city and stays as long as possible, losing oneself in the complications of streets rich and dirty with time. As the seedbed of existentialism, with half of the humanist tradition buried in Père Lachaise, it is also the place to find oneself. Its atmosphere has been mythologized to the point of absurdity because of the search the city promises, one of both angst and joy—the paradoxical resting point for compulsive wanderers.

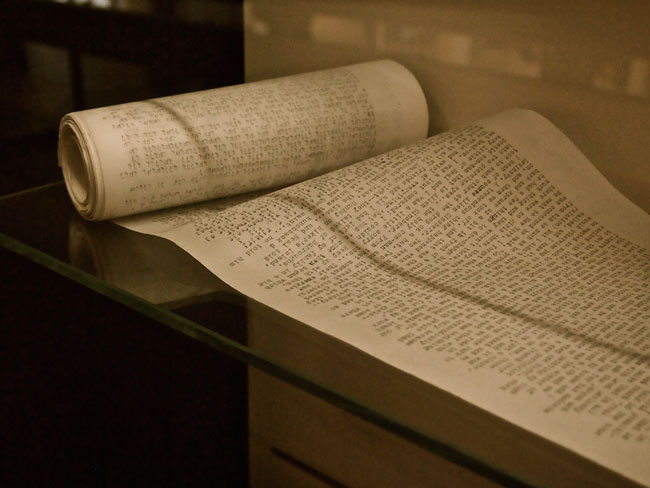

Paris is also, until August 19th, the place for Junior Beats to find their mandala: the legendary original scroll of On the Road, that hundred-word-a-minute novel sweated out by Jack Kerouac. His reputed masterpiece can be found in the small anteroom of the Musée des Ecrivains et Manuscrits at 220 Blvd Saint Germain.

About twenty feet of the scroll is laid out straight under glass, the rest rolled into thick hunks at both ends. The section presented is a straight block of text—on and on, a gray chunk that wanders relentlessly down, without the white space of paragraph headings or chapter breaks. Pages are connected every fifteen inches or so with strips of shiny tape. There are brief smudges here and there, penciled corrections that have faded almost to the color of the paper. The typed words are still legible, fiercely stamped with a mark both physical and textual. Letters ripple in the light, each one engraved by the imprint of a machine.

The rest of the exhibit features flimsy memorabilia of the Beat road trips: letterbag, typewriter, first editions, map and timeline, a smattering of photos from the recent movie. I try to look at the filler stuff but it all feels a bit too precious, nostalgic hoaxes collected in order to puff the room out. The scroll, as the centerpiece, commands all attention. I start at the top and read the whole of the visible text.

I must admit: I’ve never read the book.I used to dislike the Beats intensely. After moving from the East to West Coast at the age of thirteen, I didn’t appreciate the lack of history, the non-specificity of place that California presented. That which was supposed to liberate proved the opposite—I was unimpressed by the straightened highways, teaming with strip malls on either side. I didn’t take well to the myths surrounding their names—Burroughs shooting his wife, Ginsberg’s shouted “holy”s one after another, recklessness for the sake of pure pleasure, stragglers in the dust. As I began nursing literary pretensions in high school, I decided that I liked crafted prose, sentences with muscle, language obsessive to its task. I wrote the Beats off as speed-typed cluster-fucks of language, masturbatory spreads.

I had read Kerouac’s Tristessa at the suggestion of a friend and felt it to be raw, oozing carelessly across the page, the heroine idealized and then demeaned, her very name reduced to atmosphere and emotion.

So I went to see the manuscript not so much to pay tribute, but rather distantly curious about the French perspective on such a prototypical American subject matter. And to see a glimpse of the Bay Area, where I live, in Paris, where I find myself this summer.

But I found that now I had started down the road, Iwanted to continue. On my way home I picked up a copy at Shakespeare & Co., the unedited version published by Penguin in 2007. Scroll now in hand, I began to read.

The manuscript text is breathless. Ellipses have two periods instead of three, a missed punctuation mark revealing the urgency of the recording process. The whole of the book could have been written in a singular exhale. One feels the act of writing contained in the words themselves, the three weeks when Kerouac sat down and spat it all out, constructing the scroll beforehand because he didn’t want to have to stop to change the paper, his wife bringing coffee after coffee in order to fuel the sleepless nights, rotating sweaty shirts as the frenzy of his writing soaked one after another.

Even as I sit on a park bench, comfortable in the sun and breeze, it is impossible not to get swept up in the energy. Reading the book urges conflicting impulses. On one hand I want to keep at it relentlessly, not lifting my eyes until the pages end. But On the Road is, if anything, a call to get on the road, to jump off the couch and walk out to the nearest crowd of people. The city becomes a promise, a promise that must be taken up with “immense vistas of the plains behind every sad street.”

Space and time collapse and then converge as everything between one place and the next is accounted for with a speedometer. Neal Cassidy drives from New York to Denver, pulls up to the porch with a “Hey there,” as if he had just been out to get some pop. The sixteen hundred kilometers from Denver to Chicago is made in a matter of hours on the wheels of a stolen car. The pursuit of the open road becomes an illicit one; the travelers want to cheat the clock, cheat the distance and, if that wasn’t already too much to ask, ultimately cheat death. “Life is not enough,” wrote Kerouac in a 1949 diary entry; On the Road makes you feel like it maybe can be enough, as long as you keep on reading and driving (going, going).

As time and space converges, the people do, too. In every roadside diner or jazz joint in the slums, there is a close childhood friend or former flame. And even if you don’t know anyone, you will get to know them. Formalities of both etiquette and syntax are forgotten as connections are made from person to person, word to word. No need for definite articles or polite banalities. For the traveler, those far from home, the idea is a beautiful one—that, after a few bucks spent on beer, strangers can become friends and the night ends in revelry for all.

This doesn’t mean that the road is an easy one. The book starts with the death of Jack’s father; a search for the Father is perhaps what prompts it all. Those who romanticize about it haven’t paid close enough attention. Every penny is accounted for; dinner is canned spaghetti or nothing at all. People sport bruises on their arms and cheeks from lovers’ quarrels, tired and exhausted of each other and the world. Casualties are noted with the name of each girl left behind, and there are many—a stream of escaped motels. The Gatsby-like Cassidy might pick up and leave, but Kerouac remembers, and wants us to remember, that people were lost or hurt along the way.

Highways are crossed one after the other on impulse; the text records a cartography of human love and desire, misdirected and confused as it is. The journey is taken up, motives unknown, destination yet to be determined.

The book begins in springtime, with “everyone ready to go on some trip or another.” It’s like the prelude to Canterbury Tales, with people tapping their toes on the stoop, yearning to get out, get away, go and see something. In those days, the posture of a pilgrimage could be taken up. Now the journey is that which is must paid tribute to; without a destination, the means must become the end in itself, pretenses be damned.

Kerouac never found his hoped-for answer, his transient destination. The search went on after his return to New York; San Francisco proved an insufficient answer to the search “for joy, for kicks, for something burning in the night.” All those road trips weren’t enough. He had to sit down and write about them, eventually changing the details of plot and players so that the novel strayed further and further from reality.

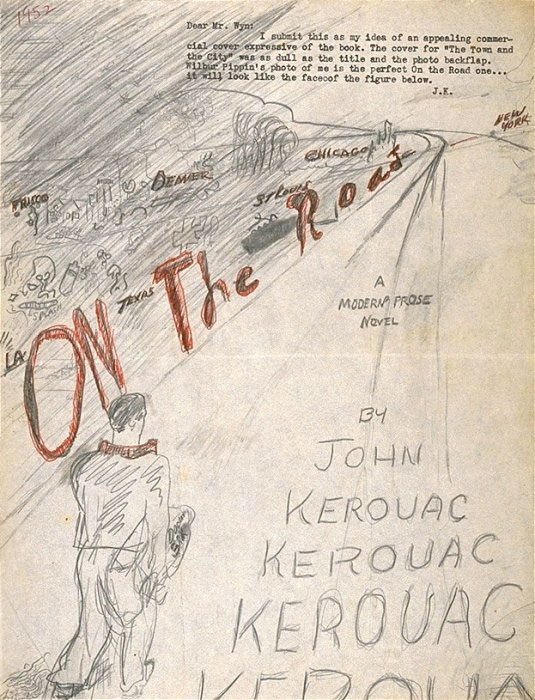

Jack Kerouac's original sketch for the cover

On one of his hitchhikes Jack pulls out a map and consults the driver about the best way to get to the coast. The route, originally mapped out in a straight line due west, has to be modified with various bends and deviations. “It was my dream that screwed up,” he says, “the stupid hearthside idea that it would be wonderful to follow one great red line across America instead of trying various roads and routes.”

The road foundon the manuscript is that dotted line; it tries to reconcile that which happened with that which was hoped for. One has to remember that Kerouac has, at that point, given up. He is stationary, at home. The urgency of the text is partly felt out of desperation, trying to reclaim what was lost, burned up in the exhaust of cars. On the Road becomes an elegy, celebratory and mournful at the same time.

I’m not sure how to straighten Paris out. Its clotted streets have been both invigorating and confusing. I came looking and hoping for a lot, and I don’t know if I’ve found it yet, and I don’t know if I will. But here, in San Francisco via Paris, in a home found through dislocation (of place, of narrative), I can take up the urge like never before.

Summer is almost over, and at the end of August I return to that white city on the West Coast. “Here I was at the end,” Jack says upon the sight of the Pacific Ocean “no more land. And now there was nowhere to go but back.” Yet in going back, in taking pen to paper, perhaps one can begin again.

You must log in to post a comment.