By Patrick Errington

Sacha Guitry, a Russian-born French dramatist and actor, said famously, “Être parisien, ce n’est pas être né à Paris, c’est y renaître,” (“To be Parisian is not to be born in Paris, but reborn”), a statement that probably unifies the artists of Belleville, the loosely defined quarter that dribbles into the 10th, 11th, 19th, and 20th arrondissements of Paris.

Belleville is unique in Paris. Not architecturally, no—like most of the city it saw the sculpting hands of Baron Haussmann and his disciples who created the large boulevards and cut swathes through the lacework of little streets and opened the verdant slopes of the Belleville hill to its two main parks. But with his demolition of the inner-city side-streets and slums, Haussmann caused an exodus of the working class from central Paris to the newly annexed “city” of Belleville. And this feeling of remoteness and community is still felt in this neighbourhood.

Part of what gives Belleville its charm is its multiculturalism. Since the early 20th century, its working-class atmosphere and consequently lower rent prices have drawn many immigrants, from the Ashkenazi Jews and Spaniards in the 1930s to Tunisians, Algerians and Chinese in more recent years. (In fact, as a result of this cultural mish-mash there have been reports of disputes or even “gang wars,” but after a year of living there, I saw no real evidence of this.)

Lower costs also attract artists. Like in the famed Montmartre during France’s Belle Époque, or Montparnasse in the days of Hemingway, Fitzgerald and the other artist expatriates between the great wars and before the marring modernizations of the 1960s and ‘70s (and the oppressive monolith, the Tour de Montparnasse), cheap living in Europe’s most inspirational city has been the candle around which so many moths flutter.

Before continuing, I should clarify. One cannot deny that Paris—all of Paris—is teeming with artists of every sort. Walk along Montmartre with your eyes closed and before you fall down any stairs you’re guaranteed to trip over a half-dozen painters, caricaturists, or musicians. Or in the twisting alleyways between St. Germain-des-Près and the river, or in the bouquiniste’s boxes along the Seine itself, there is ample evidence of artwork being conceived, created and commoditized. But these are not the artists I was looking for. Those most often seen in Paris are the established few who are earning vast sums, or schools and universities on the (now significantly reduced) stipends of governments, or those doling out five-minute watercolours of Notre Dame or sketches of the Tour Eiffel evolving into a giraffe or caricatures of tourists as wide-eyed monkeys by the dozen. I wanted the ones pushing boundaries, those making art because they love it, because there is no other way. I found those people in Belleville.

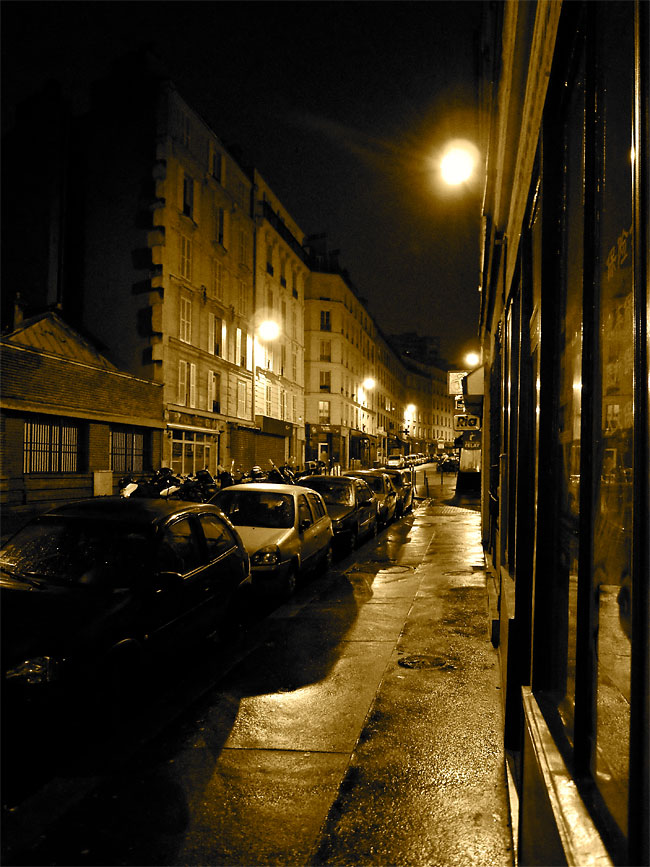

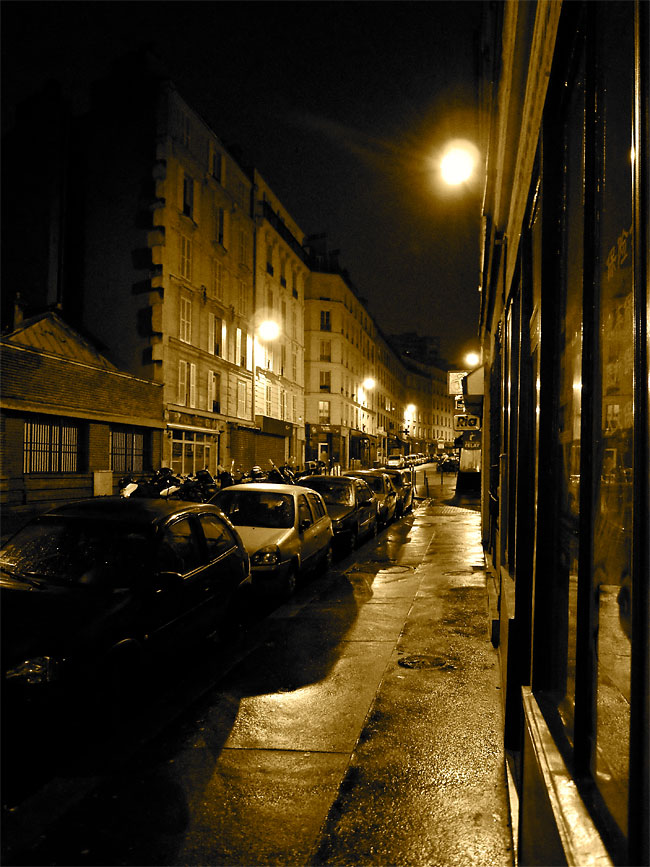

You have to look, of course, but not hard. While not as pearly-white and polished as more central locations in the city, yet with none of the tourist frenzy, Belleville can be off-putting at first. But after a few moments, once you escape the hubbub and thronging mix around the métro station, you’ll find yourself slipping in and out of sinuous side-streets as if they were water, strolling avenues that have escaped so many modernizing and cleansing touches, places that seem, despite the cellphone shops and internet cafés, as if they are part of a Paris only read about or seen in photographs and sepia-tone.

That feeling is what attracted metalworker, jeweler and stained-glass worker, Hélène Vitali to her workshop location at 28 rue Jean-Moinon, just north of Belleville station.

“This part of Paris still has spirit,” she explained, indicating the tiny street out her shop window that slopes down toward the old Hôpital Saint Louis.

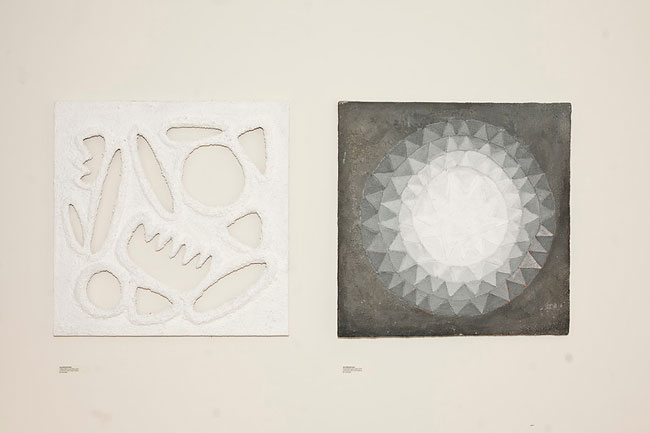

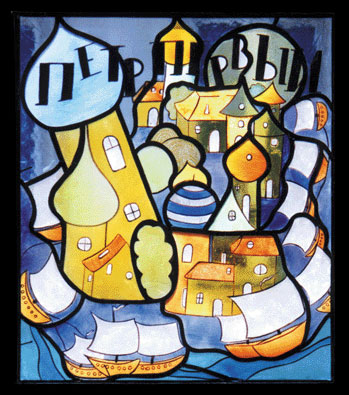

Behind the red-boarded exterior, her shop is tiny, filled to overflowing with metal and glassworks. One of few people I’ve found who was born and raised in Paris, her pieces are a fascinating and modern, a mix of traditional materials and very contemporary shapes.

“There are very few people still making art with stained glass, with copper, with steel,” she states. “What I do is take really old materials, things people have been working with for hundreds of years, and use them in new and interesting ways that people have never thought of before.”

Vitali’s formation was as an apprentice in traditional glass-staining techniques. It was while working as a restorer of windows for churches and cathedrals that she began experimenting with her own designs. Here, she was working on a mirror, an oval shape framed by a steel and copper and melted lead that looked like droplets.

“This is what I love doing,” she indicated the edges, “taking something functional and making it into art.”

She shows me several other examples, including a table lamp with a shade made of stained glass fragments.

“Making money, though, is what’s hard,” she says.

Tucked away in a small alleyway in Paris, it’s easy to understand. She tells me that she exhibits in other locations and that she also makes things to order, indicating a series wall-fixtures that she is constructing for a new bar in the area. She also makes and sells jewelry. This place, she says, is just her workshop.

I asked her why she has her workshop here, why Paris.

She laughed, “Belleville, because it’s cheap. And because this city is all old materials used to make something new.”

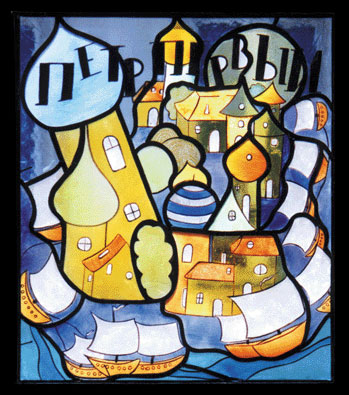

Turning traditional on its head is just what Adriana Popović does, too. Located just down the road from Vitali, Popović’s work follows a similar thesis but in a very different direction. She is a sculptor because she has “always loved the material.”

Daughter of a renowned surrealist painter from Serbia, Popović grew up in Paris with art in her blood. Her pieces too, touch on the surreal, the fantastic. Like the more tortured sculptures of Rodin, the more abstract, her sculptures are full of movement, seeming to twist or writhe on their platforms.

She explained how her work grew out of an expanded reality, a reality of the mind, rather than the sensory world. Influenced greatly by surrealism, artists like William Blake, the realm of nightmares, of the fantastic, the semi-mythological, all imbue her darkly coloured pieces with a turbulent, dreamlike quality.

Like Vitali, Popović turns to more functional pieces, though, to earn a living. Using similar methods to her true interest, she sculpts dishes and vases, glazing them in more colour and adding only a few twists to the edges, a little reminder of the skill she hides in them.

In a way, Belleville has become like those plates, its purely functional façades (as purely functional as anything gets in the architecturally extravagant Paris) encasing so many talented artists. So many workshops are walked past every day in Belleville, few people even guessing at the fascinating people at work just behind the doors.

Were it not for the early dark of winter and the warmth of the light inside, I might never have ventured into the workshop of Angelo Aversa, never discovering one of the most fascinating artists along the place Sainte Marthe, just one block from Vitali and Popović.

Emigrating from Italy, where he was raised in and around Naples, Aversa found his home away from home in Belleville.

“This area is like a village, really,” he explained. “It’s the only place in Paris I think I could really live. It’s international,” he exchanges waves some people passing the window, “everyone knows each other—there are five Italians within 20 square meters!”

With true small-town hospitality, he had invited me inside his small shop, made us coffee and offered me a plate of biscuits.

“I’ve seen pictures of Paris—old pictures, from a hundred years ago,” he continued. “This quartier looks a bit like that.”

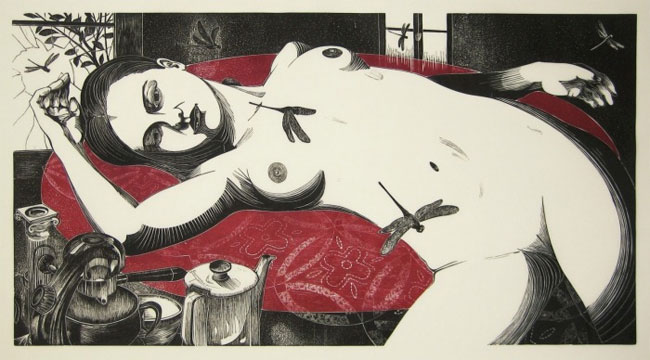

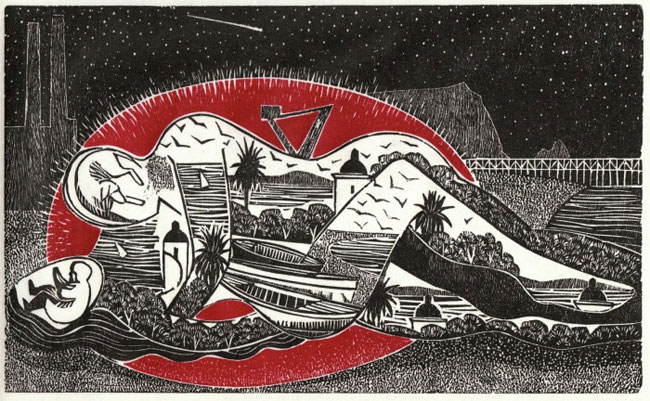

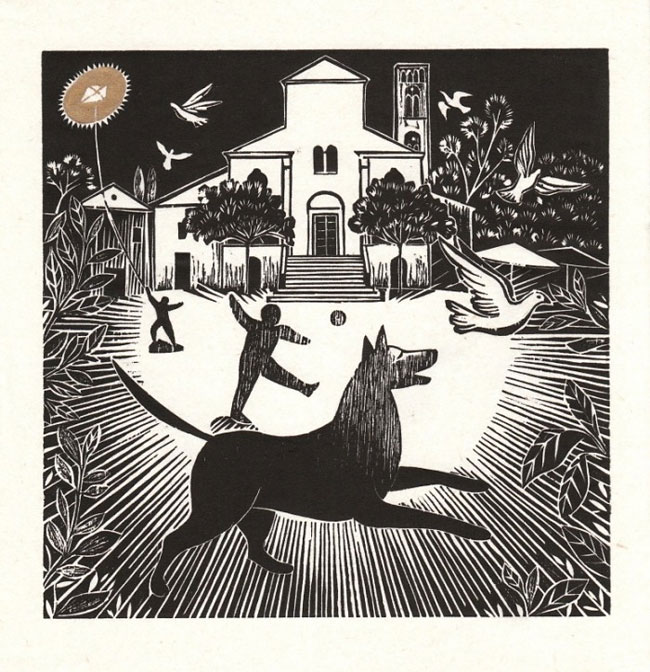

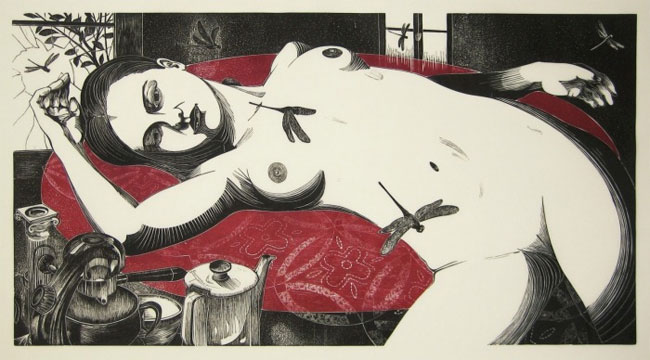

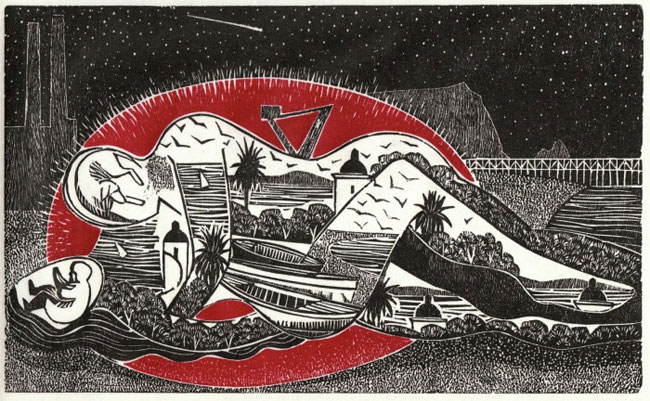

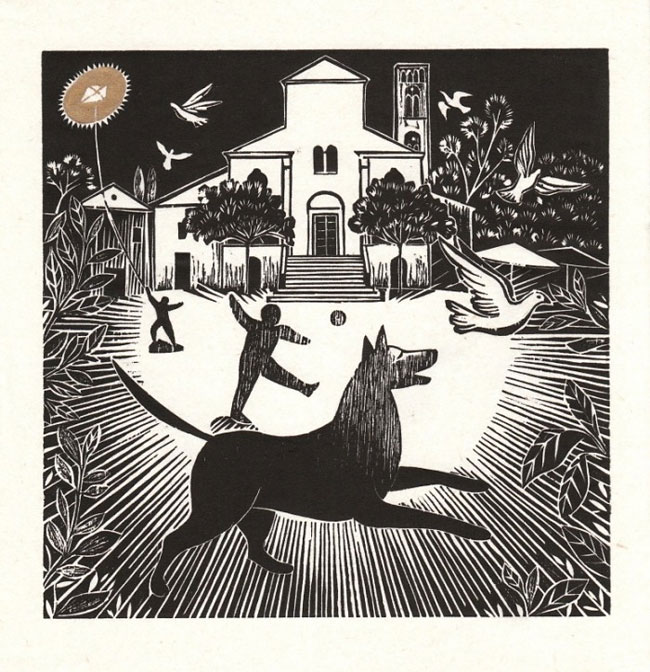

Aversa’s work is almost exclusively prints made from woodcuts. Using soft woods, he carves a stamp which, with mostly red and black inks, he uses to stamp a picture onto Japanese paper.

“I still think it’s a miracle that people want to buy the things I create,” he laughed.

Having quit school at fourteen, Aversa turned to art. He first learned traditional Renaissance-style painting as an artist’s apprentice and studied at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli in Naples.

“But the most important lesson as an artist is to unlearn,” he added. “You have to learn and learn and learn, and then, eventually, you just have to forget it all and do what you do.”

When asked about his influences, he replied, “You just have to develop your own style—just by doing. Start simply. Just draw something, then do it again a little different, and keep doing it and you’ll find your style.”

It was in Paris that he met his wife, who was visiting from Boston and who bought one of the prints that he was exhibiting. It was she who first showed him the neighbourhood of Belleville and he was captured by the magic of it, despite its somewhat run-down nature. She now shares the studio with him, using the space for her fashion business and him using it to exhibit his pieces.

“She is a real source of inspiration for me.” He indicates a number of striking prints. “Her and my son.”

I asked him how he liked sharing a studio with his wife and her colleagues.

“We work well together,” he said, “Though I do most of the actual working at home a few blocks away. But I never go to the fashion parties and social events. All that talking! Languages aren’t really my thing. Art is my language.”

The business side of things is not what interests Aversa either.

“You never know what people are going to like. All of my best pieces, the ones that speak to people, are ones I wasn’t sure about. They are the ones with a spirit. The ones that I thought ‘Ah yeah, I can see it, it’s going to be great!’ never sell. That is the mystery of art.”

Before I left, he brought out some of his older woodcuts to compare to the newer pieces that line the walls.

“The important thing is not to close your mind, to keep an open spirit, to never stop changing. I’m in my forties and I never know how I might change, tomorrow.”

Those words stick with me even now. Belleville is changing, as is Paris. Just down the street from Aversa, Vitali, and Popović, new buildings are going in, buildings of a modern design, of steel and wood and uncarved stone, so incongruous with the rest in the area. The prices are going up in Belleville as housing becomes progressively scarcer in the city. Economic turns are further reducing what little money goes to the arts. How long will it be until artists will no longer be able to afford workshops here? How much longer will Paris be the city of art it has so long been? How can it keep from becoming just a shadow of its glory days?

The artists of Belleville are doing their part to keep the traditions alive, to breathe new life into them, no matter their own backgrounds and upbringings. They have even started exhibiting together, Vitali, Popović, Aversa, and others, having just collaborated to launch a Christmas exhibition. In the summers, the Place Sainte Marthe, the Parc des Buttes Chaumont and others are filled with concerts and exhibitions of artwork that are so worth exploring. And the city too, is doing its part, organizing a yearly opening of the workshops of Belleville. Together they are turning old materials into new shapes.

Things are changing, there can be no doubt of that. But as they do, so artists change, so art changes. Paris will adapt, as will Belleville. And art will adapt with them. Today, Belleville may be the latest in the list of Paris’ bohemian haunts. Who knows how it might be reborn again tomorrow?

Hélène Vitali is a Parisian metal and glassworker whose jewelry and furnishings can be found in her exhibit at La Création Bastille on the boulevard Richard Lenoir (10:00 am to 7:00 pm) in Paris or on her website: art-vitrail.over-blog.net. Parisian/Serbian sculptor, Adriana Popović’s works can be found at her workshop at 22 rue Jean Moinon, and pictures on her website: adrianapopovic.tumblr.com. Woodcut prints and paintings by Angelo Aversa, can be found at 21 rue Sainte Marthe in Paris, and can be seen on his website: woodcut.weebly.com.