a list from Harriet Alida Lye

I made a resolution to read only things that moved me and didn’t always succeed, but since “move” is a pretty general term, I guess I didn’t ever really fail either.

I read Surfacing by Margaret Atwood, over New Year in Northern Ontario. It was my first Atwood – my reluctance probably due to the fact that, as a Canadian, I felt I’d already absorbed her – and the woods and that cabin and “those damned Americans” stayed with me throughout the year. I read Craig Thompson’s dazzling Habibi and came out of it different than before, believing in new things.

I read about 60% of The New Yorker – mostly fiction, little about the election. I didn’t read as much of the news as I feel a good person should. I read Tweets and lots of things on Facebook, most of which went in one ear and out the other and of those that stayed, I wish they’d leave.

I read lots of Alice Munro. A little of Hateship, Friendship Courtship Loveship Marriage, all of Runaway, and most of Dear Life, her new yet familiar collection, and felt glad for Alice in every line.

I read Chatwin’s On the Black Hill after a trip to Wales, and The Sense of an Ending, and felt I could have done without either, though both reminded me of my father. My father gave me The Girl in Blue, my first Wodehouse, and that reminded me of him, too.

I reread White Teeth, having remembered only that I loved it, and loved it all over again; I reread bits of Just Kids just to remember why I do all this, and reread This is Water for the same reason. Reread Franny and The Virgin Suicides to remind myself of what I love about writing.

I read To Kill a Mockingbird for the first time, and read the whole story aloud to my special friend in an accent I personally think was alarmingly Southern (alarming since I’ve never been South of Virginia). I read George Saunders’s short stories and his short novel, The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil, and preferred the stories. I read Fall on your Knees and felt Canadian and sexual and naively excited by both of those things. That scene in Central Park is, well, hot times.

I re-read my own first novel, rewrote half of it (then rewrote it again), and then wrote a second novel just to escape the first. For the second book, I read lots about bees and Canadian history. I read novels by two of my dearest – Rosa Rankin-Gee and Nafkote Tamirat – and felt privileged to know these people personally.

I read most of Rabbit at Rest, the final in the quartet, and while I love Updike mostly, I found myself bored and defensively feminist, so stopped after the (warning! spoiler!) heart attack. Same disappointment with another favourite: Ondaatje.

I read Canadian heavy-hitters The Sisters Brothers and Half-Blood Blues, and now memories of Oregon during the gold rush and Berlin blues bars during the war feel like my own.

I read loads of submissions – short stories and poems and essays – for this magazine, the surprising and beveled gems of which are published in issue 12, and I read novellas for the Paris Literary Prize, for which I am helping separate the wheat from the chaff.

I read, loved, and constantly misquote This is Not the End of the Book. Read it if you want to feel like you’re attending the most interesting private dinner party; read it if you want to be more interesting at your own private dinner parties.

I read Never Mind by Edward St. Aubyn and found it rolled off the tongue but was too full of hateful things to continue with the series. I read Carol Ann Duffy’s new and beautiful collection, The Bees, to purge myself of all that undirected and inward spite from Never Mind.

I often tried to read the weather and always failed. In Sweden, the locals tried to teach me to read the birds but I failed here, too.

{ 0 comments }

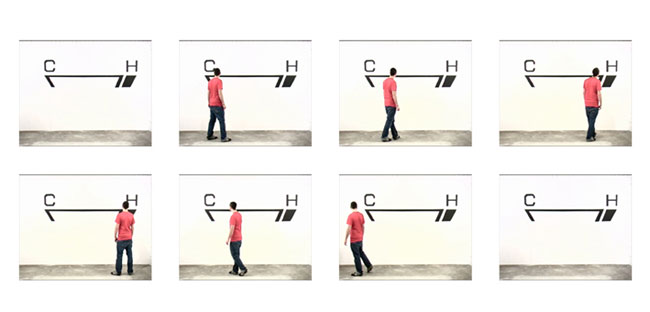

There’s a Confucius quote that goes something like “the man who moves a mountain begins by carrying away small stones.” Kyle Hughes-Odgers is the exceptionally talented Perth-based artist who is carrying these small stones. He is always working, chipping away at creating new pieces, and then all of a sudden you realize that the whole mountain’s been moved – as if it happened overnight. But that’s what being productive and dedicated often looks like from the outside. As if overnight the success story has been written when in reality it’s been a long time in the making. Kyle is an inspiration when it comes to achieving and staying focused. In the last year alone, he’s held his first European solo-show, painted in strange locations around the globe, and illustrated his first kid’s book.

There’s a Confucius quote that goes something like “the man who moves a mountain begins by carrying away small stones.” Kyle Hughes-Odgers is the exceptionally talented Perth-based artist who is carrying these small stones. He is always working, chipping away at creating new pieces, and then all of a sudden you realize that the whole mountain’s been moved – as if it happened overnight. But that’s what being productive and dedicated often looks like from the outside. As if overnight the success story has been written when in reality it’s been a long time in the making. Kyle is an inspiration when it comes to achieving and staying focused. In the last year alone, he’s held his first European solo-show, painted in strange locations around the globe, and illustrated his first kid’s book.

Les Mangeurs de Lotus Bleu, by Mia Funk

Les Mangeurs de Lotus Bleu, by Mia Funk

Pastel, by a student of the Académie Julian

Pastel, by a student of the Académie Julian