Reviewed by: Elysha Chang

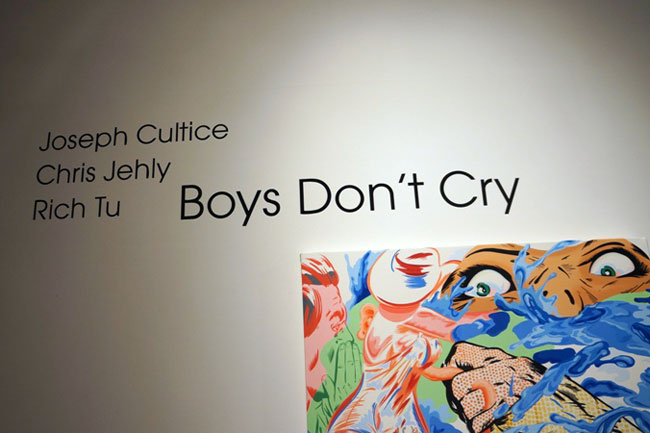

On October 4, 2012, I trekked to Manhattan’s far West Side for the opening reception of Boys Don’t Cry, a debut of Baang and Burne’s three newest additions. Boys Don’t Cry features Joseph Cultice, Chris Jehly and Rich Tu, three visual artists working with different mediums and very different aesthetics. A sort-of interconnected triptych, the collection is meant to give us a glimpse into the emotional/intellectual expanse of a boy’s (man’s?) life.

Boys Don’t Cry investigates male desire in all its forms. What is want? What happens when it is fulfilled? Not fulfilled? What comes from too much desire, too little? What is impulse versus hunger versus longing? Through paint, drawing and photography, Cultice, Jehly and Tu broach questions, fears and hopes that, according to the show’s intent, reveal the richness of the male mind.

Cultice’s photographs linger in a way that the others do not. There is something deeply nostalgic and melancholy, that his pieces seem to feed off of. Jehly’s pieces were striking for their chaotic nature, demanded our attention for as long as we could bear to look. Meanwhile, Rich Tu’s pieces were cordoned in a red-walled room on their own. I’d seen them before, several months ago at his own show, There Will Be No Survivors. Seeing them now in the context of these other pieces made it a different experience. This new environment brought his wit and conceptualism to the forefront. Alongside Cultice’s lush photos and Jehly’s chaotic, absurdist drawings, the simplicity and control of Tu’s pieces refreshed a gallery that was swimming with color, people, paint, wine, and sweat.

That is to say, it was really crowded and hot in there. Amidst the other white-walled, enhanced-echo galleries in 548 W 28th, Baang and Burne’s space stood out that night for its exposed piping, unfinished ceilings and poor air ventilation. It was teeming with young artists and art connoisseurs whose faces were beaded with sweat and whose hair might best be described as anti-coifed.

Which is, partly, what Baang and Burne is going for. A self-proclaimed “unconventional art gallery with the spirit of an indie rock band,” Baang and Burne is meant to be a refuge from the highly commoditized world of contemporary art. According to its mission, the gallery’s goal is to showcase art that is culturally subversive, that is challenging, that engages people and connects them with one another. One of Baang and Burne’s main differentiators is that it prioritizes showing art over selling it.

A friend and I were introduced to the gallery’s Co-Founder and Executive Director, Charlie Grosso. She had high, bright cheekbones and a suppressed smile. She was dressed in a simple black shift, sipped red wine from the nice kind of plastic cup. We asked the typical questions (What is your favorite piece in the show? Has anything sold yet? How do you select the artists you represent?). She answered dutifully, and then turned her attention to what interested her, offered some details about a publication’s recent criticism of her swift accrual of three young, male artists to the gallery’s roster.

“We were critiqued for being female minority directors and bringing on three male artists in the last six months.” She rolled her eyes, confident and nonchalant. “To me, it’s about the art, and what we like in the art. If they’re men or women, so what? None of that matters. It’s about the work and if the work suits the mission of the gallery.”

While the show’s title is gendered, the art itself is not. Boys Don’t Cry is an expression of human desire in all of its crudeness, its inanity, its beauty, its confusion, its art.

Boys Don’t Cry is up until November 8, 2012.

You must log in to post a comment.